Assessing parenting is a complex. It requires capturing nuanced, multifaceted behaviours within the unique context of each family. For clarity and efficiency, many assessment frameworks have historically utilised straightforward three-point scales.

While these systems provide a high-level overview, the field of psychometrics (the science of measurement) indicates that simpler scales can struggle to capture the gradations essential for a truly precise and fair evaluation. Oversimplified grading may not adequately distinguish between minor, coachable challenges and more significant concerns, or between adequate care and truly exemplary parenting.

Informed by this research, the team at FamilyAxis has implemented a dedicated six tier grading system. This article outlines the evidence supporting this choice, demonstrating how a more granular scale enhances the precision, fairness, and supportive potential of parenting assessments.

Key Takeaways

- Built on Robust Evidence: Psychometric research consistently shows that scales with 5-7 points offer higher reliability and validity than 3-point scales.

- Designed for Fairness & Precision: A six-point system helps reduce rater bias and provides clearer behavioural anchors, ensuring different assessors can grade the same observation consistently.

- Enables Proactive Support: Nuanced data helps identify subtle positive trends and emerging challenges early, allowing for more timely and tailored interventions.

- Strengthens Evidence-Based Practice: The detail captured provides a rich, defensible evidence base for court reports and supervision, moving beyond a simple binary of "met" or "not met" standards.

The General Science of Rating Scales

Extensive research in psychometrics (studying the theory and technique of measurement) has investigated the optimal design of rating scales. The consensus is that the number of scale points significantly impacts its accuracy and usefulness.

Broad reviews of the literature find that while 3-point scales are simple to use, they have inherent limitations in statistical reliability and their ability to discriminate between different levels of performance. Studies show that increasing the number of points above three dramatically improves both the consistency between different raters (reliability) and the scale's ability to measure what it intends to (validity).

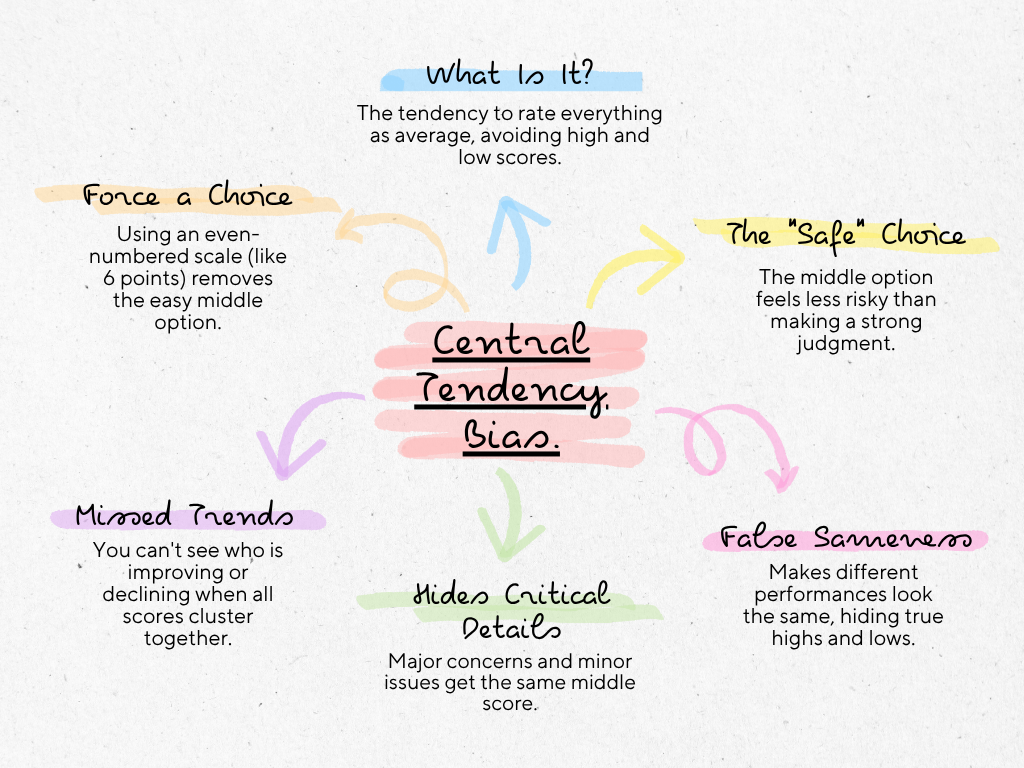

This is because with only three options, raters are often forced to cluster observations in the middle category, a phenomenon known as "central tendency bias." This can make it difficult to distinguish between a minor issue and a more significant problem, as both might be categorised under the same broad term.

The Value of a Detailed Grading Scale

The move towards more detailed assessment scales is already well-established and researched in other fields:

- GCSE Reform: The UK moved from an A*-G system to a 9-1 scale for GCSEs specifically to "provide greater differentiation," particularly between high-achieving students. This acknowledges that finer distinctions provide more meaningful information about abilities.

- University Degrees: The UK degree classification system uses multiple tiers; often discussed in terms of First, Upper Second, Lower Second, and Third—precisely because these nuanced distinctions provide employers with vital information on a graduate's capabilities, with data confirming they correlate with different career outcomes. This demonstrates a long-standing recognition that important decisions require more than three grading categories.

In parenting assessments, this principle is just as critical. Distinguishing between a parent who provides a "Good Foundation" (adequate, safe care) and one who demonstrates "Excellent" skill (proactive, sensitive, and attuned care) provides invaluable information. It allows practitioners to accurately evidence a family's true strengths and pinpoint the exact level and type of support required, facilitating a genuinely strengths-based approach.

Benefits of the Six-Tier Grading System

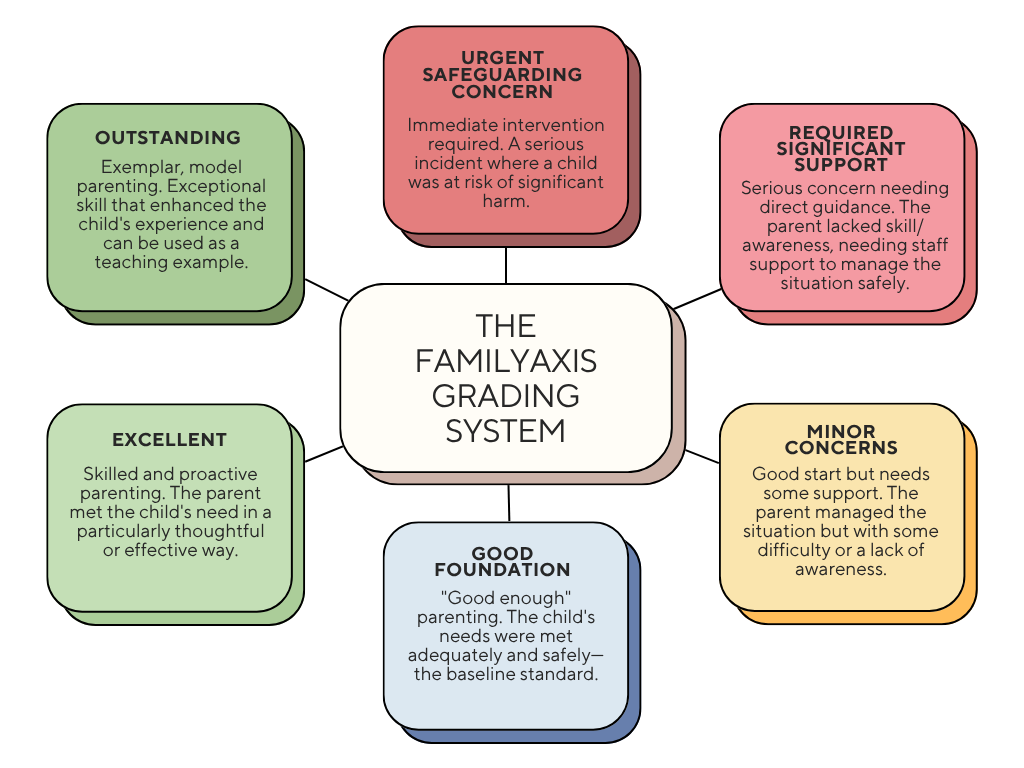

Our six-level system (from Urgent Safeguarding Concern to Outstanding) is designed to translate this research into practice. Each grade has clear, behavioural descriptors, which:

- Improve Consistency: By giving assessors more defined anchor points, we increase the likelihood that two different practitioners will grade the same observation in the same way. This reduces subjective bias and builds a more robust evidence base.

- Unlock Powerful Analytics: The granular data allows our analytics to spot subtle trends over time. A gradual improvement from "Minor Concerns" to "Good Foundation" or a slight decline from "Excellent" to "Good Foundation" becomes visible, enabling proactive support long before a more serious concern arises.

- Provide Richer Evidence for Court: In formal proceedings, being able to present a detailed, nuanced analysis of parenting—backed by specific observations mapped to a precise scale, demonstrates a thorough and defensible level of critical analysis.

Conclusion

Our choice of a six-point grading scale was not made to critique existing methods, but to embrace an evidence-based standard for precision in assessment. By leveraging established psychometric research and parallels from educational assessment, we have built a system that we believe is fair, reliable, and supportive for families.

It allows professionals to capture the full spectrum of parenting behaviour, providing the detailed insights needed to craft truly individualised support plans and to build the strongest possible evidence for their professional judgements.

Sources

- Balmford, G. (2025, June 25). Tips for managing biases in your social work practice. Community Care. https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2025/06/25/tips-for-managing-biases-in-your-social-work-practice/

- Casita. (2021, July 20). Explaining the UK grading system. Casita.com.https://www.casita.com/blog/explaining-uk-grading-system

- Hoyt, W. T. (2000). Rater bias in psychological research: When is it a problem and what can we do about it? Psychological Methods, 5(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.64

- Jadhav, C. (2017, August 10). Why 9 to 1?Gov.uk. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://ofqual.blog.gov.uk/2017/08/10/why-9-1/#:~:text=Responses%20were%20mixed%2C%20with%20some,differentiation%20at%20the%20top%20end

- Preston, C. C., & Colman, A. M. (2000). Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica, 104(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-6918(99)00050-5

- Psychometrics. (2011). ScienceDirect. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/psychometrics

- Sauro, J., PhD. (2019, August 14). Is a three-point scale good enough? MeasuringU. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://measuringu.com/three-points/

- Sauro, J., PhD, & Lewis, J., PhD. (2020, May 20). Rating scales: Myth vs. evidence. MeasuringU. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://measuringu.com/ratingscales-myth-evidence/#:~:text=2,seminal%201967%20book%20Psychometric%20Theory

- Smith, M., (2025). Impact of degree classification on early career outcomes. In PROSPECTS Luminate. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://luminate.prospects.ac.uk/impact-of-degree-classification-on-early-career-outcomes

- Statistic How To. (n.d.). Central Tendency Bias: Definition, Examples. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://www.statisticshowto.com/central-tendency-bias/